The recent mass violence and tragedies that have befallen our country are in the forefront of our minds and those of our fellow countrymen. Whether you believe that “Black Lives Matter”, “Blue Lives Matter” or “All Lives Matter”, I don’t think that you can argue that these events have affected you in a deep and disturbing way.

I bear witness to all manner of discussion and debate about what has been going on and who is to blame. At times I find myself a participant in the discourse, but the only things that most of us have been discussing are race and bad policing. And in my opinion, we are overlooking a most vital piece of the puzzle.

I am an African-American woman, and I will tell you with no uncertainty that I feel that race is certainly at the heart of much of what has gone on. I know this deep in my soul, and no one can convince me of anything different.

However, as a physician, I look at the pattern in which so much violence has occurred, and I wonder why we aren’t discussing a most relevant issue… a most prominent concern.

Why are we silent about mental illness?

Let me ask that again.

WHY ARE WE silent ABOUT MENTAL ILLNESS?

Why are we not examining the role that it has played in all of the violence… all of the massacres and deaths? Why are we willing to assign blame only to racism, poor police practices and gun control (or lack thereof); but not willing to look at a very common element of most of our country’s mass killings?

Do we truly feel that Micah Johnson ambushed an entire crowd of people, most of whom were strangers to him, only because he was angry about American race relations?

If this is the case, then America is doomed for sure. Imagine what would happen if everyone who was angry about race relations started shooting scores of people. I doubt that anyone would survive.

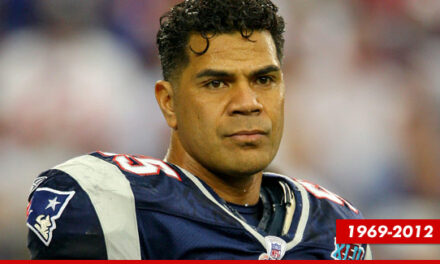

And racial tension is not the only societal ill that is impacted and magnified when coupled with mental disease. It is also the issue of bullying among school aged children and the debate over gun control.

These issues are loaded ones when analyzed as solitary phenomena; but when paired with unaddressed mental disease, these issues go from being incendiary to becoming lethal.

Recent large scale murders have crossed lines of race, socioeconomic status and religious affiliation. Out of all of our country’s mass murders, the one thread that the perpetrators have had in common is that of mental defect. Whether they suffered from paranoia, obsessive

thinking, delusional thinking, depression, mania or a full break from reality, it is undeniable that each killer was not mentally intact.

Many of us will recall the Columbine shootings in 1999. The school and the community of Littleton, Colorado became known for one of the most horrific high school massacres in the United States. The perpetrators, Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris, were professed to have endured years of bullying and alienation at the hands of their peers. What resulted were two highly disturbed young men who hatched a deadly plan for retribution. It was so deadly that they became willing casualties of it.

Unfortunately, Columbine would become the first of many school shootings in contemporary times.

There is no actual number of victims which defines or constitutes a massacre or mass killing. The FBI does not specifically define mass shooting, but it does provide a definition for mass murder.

“…a single incident in which a perpetrator kills four or more people, not including himself or herself.”

By this standard, there have been 11 other school shootings, resulting in mass murder, including two which preceded Columbine by 1 year. (This does not speak to the countless instances of school shootings on smaller scales, which take place annually.) The most notorious shootings among these have been at Virginia Tech; Newtown, Connecticut; Redlake, Minnesota; and Roseburg, Oregon with 33, 28, 10 and 10 deaths respectively.

The perpetrators all differed by race, culture, age and religious affiliation; but may have been connected by some degree of psychiatric malady prompting their planning and decision making.

And Columbine was not the first… not by a long shot. Its predecessor occurred decades prior, at the University of Austin at Texas. Charles Whitman climbed to the top of the campus’ bell tower and, over the course of 96 minutes, using a shotgun, rifles and hand guns, proceeded to kill 17 people and wound 31 others, who were walking across the campus. Prior to this, he had murdered his wife and mother at their home.

In a letter that he penned prior to the killings, he admits to having been “…a victim of … unusual and irrational thoughts.” Although it could not be proven after his death, he sounds as if he may have been suffering from some degree of psychosis or, at the very least, hallucinations and delusional thinking.

As experts began to analyze what occurred at Columbine, the FBI and its psychiatrists arrived at the following conclusions about Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris: Klebold was depressive and suicidal; and his co-conspirator was a psychopath.

Jeffrey Weise, the perpetrator of the Redlake massacre, had been diagnosed with clinical depression and as being suicidal the year prior to his attack. He had been raised in a family in which his mother suffered from alcoholism and was abusive towards him; and in which his father had committed suicide. Whether it was nurture or nature at work, there is no denying that mental disease likely played the largest role in his actions.

Seung-Hui Cho, the Virginia Tech shooter, had had a long standing history of mental illness, dating back to middle school when he was diagnosed with a severe anxiety disorder characterized by selective mutism, and a major depressive disorder. Prior to the shootings, he had been involuntarily admitted to a psychiatric facility for severe depression and abnormal behaviors.

His actions prompted much discussion and debate in the state of Virginia regarding mental health laws and where the system failed him and his victims.

Adam Lanza, the Newtown, Connecticut shooter, is believed to have suffered from obsessivecompulsive disorder and was known to have had Asperger’s syndrome. It is speculated that he may have suffered from psychosis; however, those who knew him felt that his odd behavior was due to his Asperger’s and not any other mental or emotional malady. Experts have acknowledged that autism and Asperger’s syndrome do not present with predatory aggression, as was demonstrated by Lanza in the massacre.

His autopsy revealed that he had suffered from anorexia, as well.

Obviously, his actions have spurred debate as to whether or not health care professionals focused upon his Asperger’s Syndrome and missed a diagnosis of schizophrenia, thereby failing him and his victims.

His actions also spurred the discussion regarding gun control and screening for mental disease.

I have mentioned in detail the killings, and the perpetrators, not for gory contemplation, but to illustrate the pattern among these tragedies. There was not any other single common denominator except the prospect of mental illness.

Let’s generalize the idea even further. Let’s look at other mass killings that did not take place on school campuses. Take, for example, the Aurora, Colorado movie theater shooting. James Eagan Holmes, as a lone assailant, managed to murder 12 people that night. 70 others were injured. Holmes was later found to be mentally ill, but legally sane; and to have suffered from schizoaffective disorder. Apparently, he had been under the care of a psychiatrist prior to the massacre and had been suffering from homicidal ideations for some time.

I do believe that when a human being makes the decision to kill multiple people, many of whom they do not personally know, there must exist some degree of pathology. I suppose that some would label it “evil”. And perhaps, to some, evil looks like Timothy McVeigh. Others may call it fanaticism, and to them, it looks like Omar Mateen. Yet others will call it hatred, and it will look like Micah Johnson. On a larger scale, it looks like Adolf Hitler or Kim Jong-un.

As a clinician, I believe that untreated mental illness will often masquerade as evil. And this evil can be cunning, sometimes even charismatic or charming. But, it will lack empathy and compassion. It will be devoid of a conscience and prey upon the innocent. It will think only selfishly, and always have destructive intent. We call this sociopathy, and this is mental illness. But, regardless of what we call it, it is nothing short of devastating.

So what do we do with all of this on a personal level?

First, we cannot be afraid to discuss it. And when we do discuss it, we cannot allow fear to hijack our responses. We cannot afford to validate the stigma about mental illness or to intimidate the afflicted with our judgment.

One reason that mental disease often leads to extreme behavior is that as a society, we have been reluctant to acknowledge its presence and its power. In failing to do that, we have not adequately educated ourselves about how to surmount its obstacles. Nor have we learned how to approach the subject while preserving the dignity of the individual.

In failing at that, we have unwittingly sent the message to those afflicted that we really don’t care.

Perhaps, we are trying to be polite. Maybe we want to avoid a confrontation or an offense. Maybe we want to spare the individual embarrassment.

While these are all motives that are based in compassion, we need to understand that this is classically co-dependent, and therefore, destructive behavior. Our failure to address the problem; our failure to create a safe place for the afflicted to come; our failure to remain nonjudgmental… All of this is indeed crippling and enabling.

It sends the message that we don’t give one damn, and that whatever happens will be just fine.

That must stop. We must be more courageous.

Next, we must be able to recognize when a problem and a true threat exist. We must have some level of suspicion. Denial is not a luxury that our society can afford. Again, education is key, here.

So what do we look for?

Have there been any new peculiarities in a friend, classmate or neighbor? Has someone who was previously social and engaging become reclusive? Has there been a significant change in a friend’s hygiene? Have you noticed a family member perseverating and obsessing over a perceived threat?

Of course, these are all subtleties that can be easy to miss or even easier to underestimate and attribute to innocuous causes.

After all, no one wants to believe that someone in their inner circle may be severely emotionally disturbed. And who wants to be the person to make a concerned call to a relative or to authorities? Because, what happens if we are wrong?

What we may need to start asking is,

“What happens if we are right?”

So, fear of embarrassment makes us hesitant. We rationalize, minimize and justify the oddities that we cannot otherwise explain.

“Jim is just a little strange. He’s always been a bit peculiar.”

“Ella does not seem herself, but maybe she’s just tired.”

And this is not to suggest that we need to call the authorities whenever someone’s demeanor or mannerisms make us uncomfortable. We must recognize that sometimes our discomfort is based upon our own prejudices, fears and preconceived notions.

However, I would say that if we notice behaviors, language, social media posts or comments that are threatening to us, the individual in question or anyone else, it is prudent to contact someone who can assist. If the index person is not someone with whom you have an intimate relationship, then consider reaching out to a relative of theirs, if you know one.

If this person is a classmate or co-worker, it might be reasonable to approach a counselor at school or a supervisor at work. You do not need to make allegations that you do not know to be true, but it might be prudent to involve someone who may have the power to act.

If the individual in question is a relative of your own, it certainly might be reasonable to speak with other relatives or friends who know this person well. Perhaps they can shed some light on stressors that are impacting the behavior. However, if an interventional solution becomes necessary, they may be able to offer great support.

With all that goes on today, it is difficult not to get caught up in the hysteria. We must learn to tow the line, so that we are not persecuting those who do not pose a threat, but are merely exercising their right to be different. That being said, recent events have made awareness of mental disease and the courage to seek pre-emptive assistance, components of good citizenship.

Another thing that we must have the courage to do, is to advocate for legislative change regarding mental illness and health.

Psychiatric care should not be a luxury for those with mental disease. It should be a right. In fact, I would say that obtaining psychiatric care should be an obligation for any such patient. In short, medical care for the emotionally unstable should be readily accessible and easily attainable.

Insurance mandates need to change so that once patients are admitted to the hospital for an acute psychiatric emergency, their physician is not pressured to discharge them prematurely in order to meet quality assurance standards. QA standards can impact the likelihood of successful reimbursement from the insurer, and will often compel a hospital and/or physician to discharge patients when they have been sub-optimally treated. QA standards, while meant to ensure quality care, can sometimes be utilized to ensure quantity of payment. And these two ideals are sometimes mutually exclusive of one another.

We need to lend our voices to these concerns and demand more from our legislators. Again, we must remember that citizenship can be a tool towards effective change. And our citizenship can impact mental illness and lessen the destruction and pain that it can cause.

Ask yourself what you will do. Will you blame the violence that has become so pervasive in our communities on terrorism, racism and religious fanaticism? Will you wait for someone else to address it? Or will you look beneath the surface to consider other causes and solutions?

Will you sit idly back and just be glad that the violence has not visited your door step? Or are you willing to impact the world around you so that we can all sleep a little better at night?